I went into the gallery without knowing what to expect. The only thing I know about the artist was that Joy said I will like his works. Who is the artist? Wolfgang laib. His name did not even ring a bell to me.

I cannot recall exactly my feeling the minute I saw the first piece. Perhaps, I sense a connection between my studio practice and that of Laib’s the moment his works came into my awareness. It was metal cones of twelve different sizes placed around the cemented floor in the middle of the room. Around them, tiny hills of rice made up the third element, a transitional agent between two hard-edged, man-made components (the metal cones and the cemented floor). Somehow, I was immediately attracted by the physicality (use of materials and the marrying of natural and manmade objects) of the piece rather than the symbolism and/or narration, if there is any, beyond its materiality. Although I would like to read more into the piece, the much distractive motion going on in the room at that moment left me no choice but to go on to other art works.

The second piece of installation totally blew my mind. In a separate room, right above my head, a wooden shelf runs across three of the walls; on the planks were rows of terra-cotta pots (400 of them, to be exact) filled with ashes resting peacefully and orderly, as if time stay still, eternally. (Actually, I did not really know what was in the pots till I read the press release. The ashes were collected from religious temples near Laib’s studio in

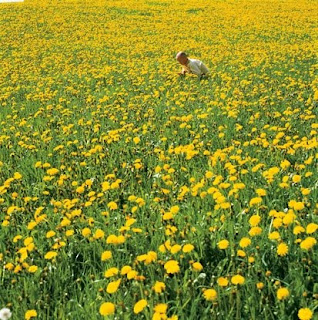

The third piece did not really strike me as much as the second one. A divider separated me from the installation and I only saw a square shape of yellow stuff spread flatly like a carpet on the cemented floor. I guess the barricade not only stopped me from going near the piece but also killed my interest to find out more about it. However, realizing later that it was done by “sift(ing) hazelnut pollen, which (Laib) has been painstakingly collected by hand in the field near his studio in

Not much was mentioned in the press release about the first piece I saw in Sean Kelly. However, Laib’s use of pollen (symbolizing the origin of life) and ash (symbolizing both the end of life and rebirth) had a much better coverage in the one page article. I walked out of the gallery with the urge to see more and know more of Laib’s. To me, there are too much unknown about the artist and his artworks. However, at the same time, there is a very strong sense of familiarity about what I just saw in Sean Kelly. It is a sense of linkage, to be exact, between my own studio practice and those of Laib’s.

I googled Laib on internet a couple of days later but was very disappointed by the digital reproduction of his other works. Not to mention the constant association I made between his works and those of Joseph Bueys’. Perhaps, if I was there to see the actual installations, in situ, I would have a much better encounter with the spiritual realm that he committed himself to. However, reading about Laib’s studio practice and his philosophy unveiled, to a certain degree, the mystery I have about him. Although much of the articles that I read were not much a different from the other, nevertheless, I do want to extract a paragraph from an article by Margit Rowell:

It is obvious that Laib’s choice of materials and his identification with their seasons, life spans, and essential properties are the manifestation of a philosophy and a way of life in which individual needs, desires, or practical concerns are of little importance. It is as clear that the painstaking attention and concentration which are necessary to control his repeated gestures in order not to violate the materials but to realize their potential purity and perfection are dictated by an extreme spiritual discipline. Thus the works themselves are the manifestation of a relation to and a vision of the world which may be defined as fundamental, holistic, timeless, rather than personal or individualistic, or related to the contingencies of a given historical time or place.[2]

Despite what Rowell said or how Laib intended to have his artworks viewed, I would say knowing where he came from, his commitment to a hermit life style, and his philosophy of being redefined my understanding of his language as well as his studio practice. I would not make an absolute connection between him and Beuys, I would not walk away from his pollen field installation with a total blank in my mind, and I would not view his art works as mere lifeless objects but records of transcendental moments in his life as an artist thinker, a sense of honesty, and a representation of the essence of being.

An interview with Wolfgang Laib on Sculpture Magazine. (http://www.sculpture.org/documents/scmag01/may01/laib/laib.shtml)

Wolfgang Laib at Speronw Westwater, Iowa. (http://www.speronewestwater.com/cgi-bin/iowa/artists/record.html?record=10)

[1] Press release from Sean Kelly.

[2] Margit Rowell (1989). Wolfgang Laib: Transcendent offerings Wolfgang Laib: Substance as essence. Fundacio Joan Miro,